Defense in Depth strategies – Part 6 – ICS Network Architectures

ICS Network Architectures

The integration of once isolated ICSs helped enterprises to manage complex environments, however, merging a modern IT architecture with an originally isolated production environment that may not have any or very few cyber security countermeasures in place introduces potential vulnerabilities which must be resolved before issues arise.

Some of the most common factors are:

- Insecure connectivity to internal and external networks

- Technologies with known vulnerabilities, create previously unseen cyber risks in the operational domain

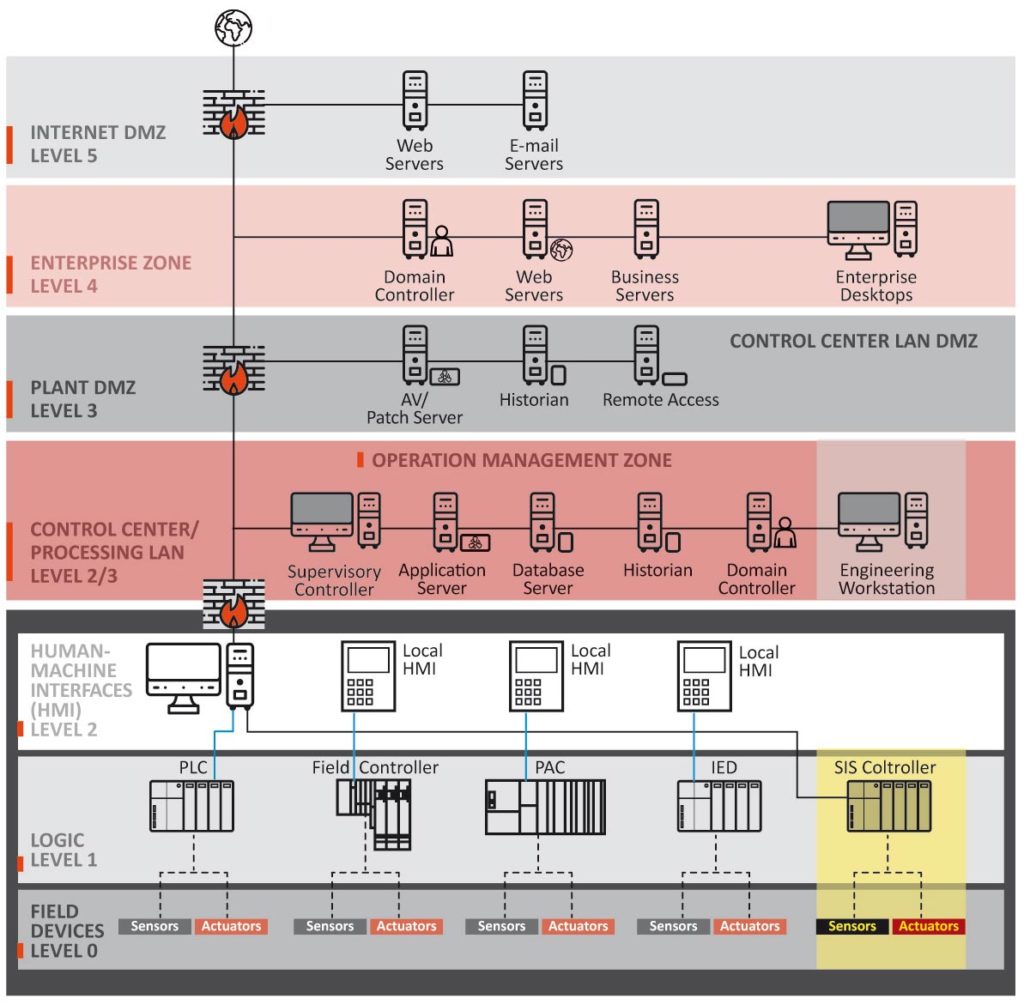

In order to countermeasure this the nowadays widely accepted integrated architecture Purdue Model was designed to define best practices for the relationship between the ICS and corporate networks. It provides guidance for physical systems architecture and introduces the six network levels of the environment, describing the systems and technologies present at each level.

Figure 1 – Purdue reference integrated network architecture model

Dividing common control system architectures into zones can help enterprises in creating clear boundaries to effectively apply multiple layers of defense.

Enterprise Security Zone (level 4)

Due to the number of systems and connectivity (including the internet) a wide variety of risks exist in this zone, and from an ICS security standpoint, should be considered an untrusted zone.

Operation Management Zone (level 3)

This zone is central to the operation of end devices and provides required connectivity to the Enterprise Zone. It is a critical area for the continuity and management of a control network.

Risks are associated with its direct connectivity to any external systems or networks and the priority of this area is high.

Cell Security Zone (levels 0-2)

The Cell Security Zone contains systems used for local or remote area control (Level 2), such as field-located HMIs, PLCs, and their controls (Level 1), and basic input/output devices such as actuators and sensors (Level 0). The priority of these zones is very high, as these are the areas where the control functions affect the physical end devices.

Each of these zones requires a unique security focus. An intruder trying to affect a critical infrastructure system would most likely go after the core control domains contained in Level 3 and below.

In an attack scenario, the intrusion begins at some point outside the control zone and the attacker moves deeper and deeper into the architecture. Layered strategies that secure each of the core zones can create a defensive strategy with depth, offering the administrators more opportunities for information and resource control, as well as introducing cascading countermeasures that will not necessarily impede business functionality.

Demilitarised Zone (DMZ)

A demilitarised zone (DMZ) is a physical and logical subnetwork that acts as an intermediary for connected security devices so that they avoid exposure to a larger and untrusted network (usually the internet). The DMZ adds an additional layer of security to an enterprise’s LAN – an external intruder only has direct access to equipment within the DMZ, rather than any other part of the network.

By placing corporate-accessible components in a DMZ, no direct communication paths are required from the corporate network to the control network – each path effectively ends in the DMZ. With well-planned rule sets, one can maintain a clear separation between the control network and other networks with little or no traffic passing directly between the corporate and control networks.

The main security risk in this type of architecture comes when a threat actor compromises a computer in the DMZ and uses it to launch an exploit against the control network via application traffic permitted from the DMZ to the control network. Organizations can reduce this risk if they make a concerted effort to harden and actively patch the servers in the DMZ, and if the firewall rule set only permits connections initiated by control network devices between the control network and DMZ.

One must be cautious when deploying DMZ solutions to connect otherwise logically separated domains. It shouldn’t be assumed that the implementation of a DMZ is a panacea for preventing threat actors from penetrating deeper into critical environments. The exploitation of transitive trust across a security perimeter is a plausible intrusion vector. However, when one develops and deploys a DMZ with appropriate security, the countermeasure will increase the work effort for the adversary, provide more granular control for the asset owner, and reduce cyber risk to vital critical assets.

0 Comments